The San Antonio Court of Appeals recently issued an interesting opinion regarding a well operator’s claim that H2S/CO2 from a nearby injection well damaged its leased minerals. The case has been appealed to the Texas Supreme Court and oral argument has been scheduled for December 2020.

The case is Swift Energy Operating, LLC v. Regency Field Services LLC. In 2009, Swift, the Plaintiff, leased approximately 4200 acres of a ranch in McMullen County, Texas and operated a number of producing wells on the ranch. In 2006, Regency obtained a permit from the Texas Railroad Commission to operate an injection well in which they would dispose of a gas mixture of concentrated hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide (CO2) by pumping it into the Wilcox formation. In its application for the permit, Regency submitted a plume model to the Railroad Commission that predicted that the injected material would spread horizontally by approximately 2200 feet after 40 years of injection. The review by the Railroad Commission staff indicated that they believed that shale formations above and below the disposal zone would prevent vertical migration of the injected gas.

In 2012, another operator in the area discovered H2S in one of the its wells and testing indicated it came from the Regency injection well. As result, that operator had to plug and abandon that well. An employee of that operator emailed Swift about these developments.

In 2014, the owner of the ranch sued Regency for trespass, nuisance and negligence and Swift intervened in the lawsuit in 2015. They requested an award of present and future damages to 74 existing or planned wells. Regency moved for summary judgment on the basis that statute of limitations on these claims had expired before Swift entered the lawsuit. Regency claimed that the two-year statute of limitations that applied in this case began when the injections commenced and that Swift knew of the possible contamination in 2012 due to the emails from the other operator. Swift contended that the statute of limitations did not begin to run until the injected material began to affect its leases. The trial court agreed with Regency and granted that motion and dismissed all of Swift’s claims.

The Court of Appeals discusses not only the applicable laws regarding the statute of limitations, but also the relative locations of the wells and the geology of the leases and the injection well. Regency was injecting into the Wilcox formation. Swift was producing its wells from the deeper Olmos and Eagle Ford formations.

The appellate opinion is interesting and more complex than I describe here and makes very interesting reading. To simplify, the Court of Appeals discussed that for trespass, a cause of action accrues (and the statute of limitations clock begins to run) when there is an unauthorized interference with someone’s rights. For negligence and gross negligence, the cause of action accrues when the injected material crossed the boundary into the leased property. For nuisance claims, a claim accrues when the condition first substantially interferes with the use and enjoyment of someone’s property.

Based on these principles, the Court of Appeals determined that as to some wells, Regency established its affirmative defense that the statute of limitations had expired, and the claims by Swift as to those wells were dismissed. On the other hand, as to other wells, the Court held that Regency had not established a statute of limitations defense and so sent the case back to the trial court for a full trial on Swift’s claims as to those wells. Swift has appealed to the Texas Supreme Court, and it will be interesting to see how that Court decides these claims.

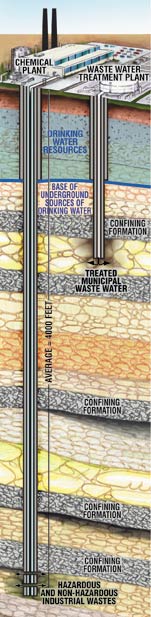

Apart from the wrangling about statutes of limitations, some folks might be concerned that the injected gases migrated beyond what the Regency and the Railroad Commission thought they would and wonder: ” what if these had been water wells that had been affected?” The answer is that the area into which the injection well placed material was many thousands of feet below water wells, which are inevitably very shallow. In my experience with the Railroad Commission, they would not approve an injection well if it was proximate, vertically or horizontally, to water tables.

Texas Oil and Gas Attorney Blog

Texas Oil and Gas Attorney Blog